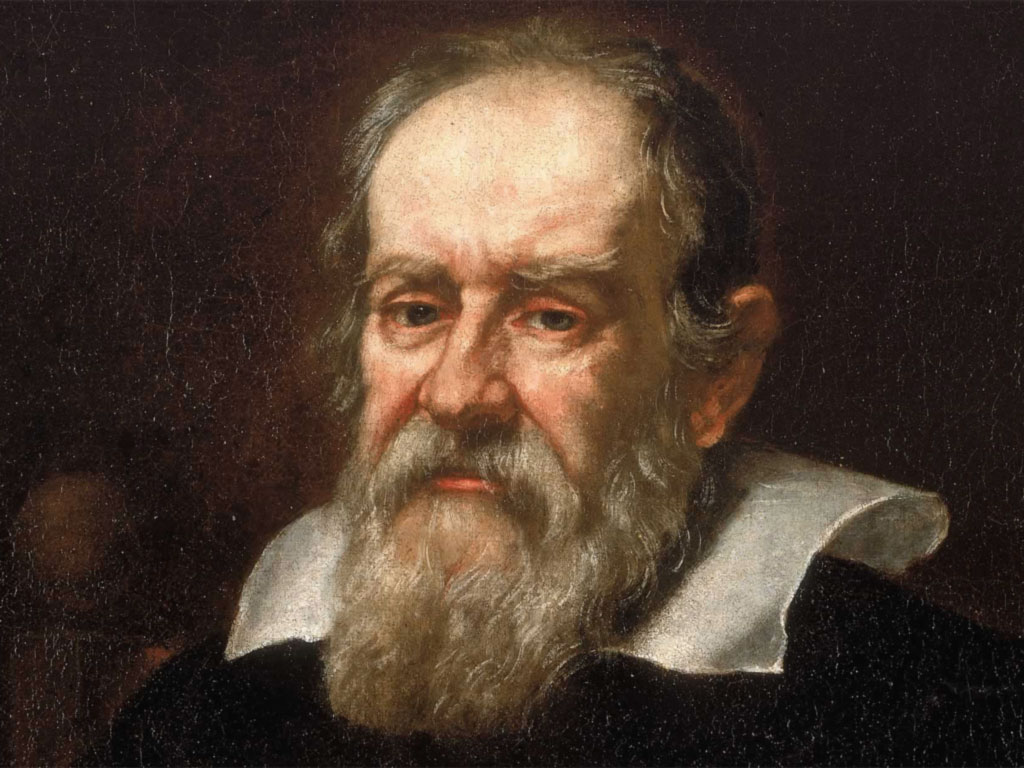

Galileo Galilei is one of the personalities that have most marked the history of human knowledge. Not considered by chance the father of contemporary science, the great scholar was born in Pisa on February 15, 1564.

The first period of scientific achievements of the Tuscan physicist was spent in Padua, where he was appointed professor of mathematics at the University. It is in Padua that Galileo adhered everyday more convinced to the heliocentric theory by Copernicus, the Polish astronomer who was the first to conceive the Sun as fixed at the center of the Universe and the Solar System and the Earth moving around it, along with the other planets.

His conviction increased after reading Keplero's "Mysterium cosmographicum". So the genius from Pisa, after having designed experiments in this regard, formulates the "Law on the free fall of bodies", sensing a proportionality between speed and distance traveled by a falling object.

After the first discoveries in the field of mathematics and physics, he decided to direct its studies towards astronomy. Two facts transform Galileo's interests in the early 1600s: the discovery in 1604 of a supernova, which rekindled the debate on the celestial phenomena; and the knowledge of the invention of the telescope in 1609. Unlike what one would think, Galileo was not the inventor of the tool to scan the sky - invented, in fact, by a Dutch, Hans Lippershey; but the scientist from Pisa was the one who improved it up to being used for his astronomical work.

The extraordinary study of Galileo produced decisive results from the scientific point of view. The scientist understood the structure of the Milky Way, the height of lunar mountains, the movements and the satellites of Jupiter, Venus and Saturn.

In 1613 his defense of the heliocentric system begins to stir controversy of theological nature. In 1616 the Holy Office in Rome condemned Galileo's heliocentric proposal, disputing the central position of the Sun and the movement of the Earth. A series of meetings with Pope Urban VIII in 1624, after the publication of "The Assayer", led Galileo to believe he could freely express his thoughts and convinced him to finish the work that will embody his much-discussed theory: "Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems", published in 1630.

But in the summer of 1632, Urban VIII decided to initiate investigations on the publication of the Dialogue. In the exchange of thoughts between Galileo and Urban VIII, the Holy Office found an unsigned memorandum that imposed to Galileo not to endorse or defend the idea that the Earth is the one moving around the sun, not viceversa. The commissioners evaluated the memorandum as effective, and then assessed the publication of the Dialogue as a transgression to the orders of the Church. On June 22, 1633, Galileo was conducted to the Convent of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome, coerced to go down on his knees, and sentenced to prison. Formally he then will retract his decision, and will spend months in Siena, hosted by Cardinal Piccolomini.

The great scientist of Pisa became blind in 1638 but continued to study, while having publishing problems due to the Church's veto. He died in Arcetri on January 8 1642. Only 392 years later, in 1992, the Catholic Church admitted "mistakes" against Galileo. 450 years after his birth, to think about Galileo in such complex times means remembering the courage of a unique talent, a shining example of the power of ideas, a worldwide symbol of freedom of thought.