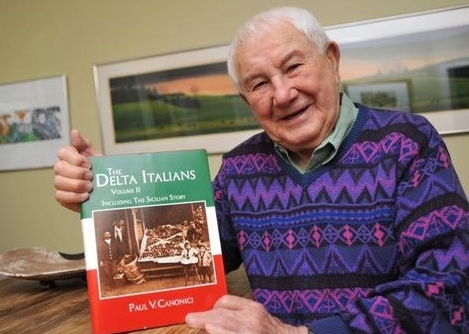

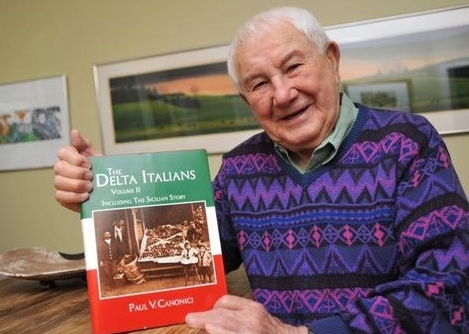

Paul Canonici (Author of "Delta Italians" Vol. I and II)

La storia degli Italiani nel Mississippi: incontriamo Paul Canonici

In our journey to discover Italy in the 50 states, today we dive between the Delta Italians, our compatriots who with great effort and sacrifice settled in the wide area of the delta of the Mississippi River, which gives its name to the Magnolia State.

The adventures of the Delta Italians described by Paul Canonici's books are intriguing and instructive: he gives us a few examples in this interview, and we are happy to give voice to a great Italian American like him, so proud of his Italianità. Thanks Paul!

Paul, you are the author of "Delta Italians" and "Delta Italians Vol. II", two books about "stories and experiences of the Arkansas and Mississippi delta plantations". Please, tell us more about these stories

My first book "Delta Italians" contains the history and family stories of those Italian immigrants who were recruited for the cotton plantations of the Arkansas and Mississippi Delta in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Most came from the Regions of the Marche and Emilia Romagna. "The Delta Italians Vol. II" includes Sicilian Italians and all other Italians who came to the Delta independently, those not recruited for cotton plantations.

The cotton plantations I am talking about are the ones in Arkansas and in the Mississippi Delta, a fertile farmland on both sides of the Mississippi River, extending from the northern border of each state, Arkansas and Mississippi, approximately 200 miles southward and inland from the River about 100 miles.

In the late 1800s Italy was united and ownership of property was transferred from the Church to individual families. The Ruspoli family got ownership of vast tracks of land in the Marche.

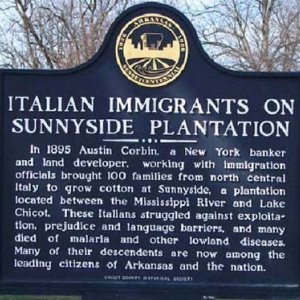

While in the Marche and in the Emilia Romagna extended families lived on small plots of land and so there was an overpopulation there, in the USA slaves had been freed and left the plantations needing of workers. In the Delta there was a lack of workers and that was behind the deal between Emanuele Ruspoli, mayor of Rome in the late 1800s, and Austin Corbin, owner or at least the man in charge of the Sunnyside Plantation consisting of more than 10.000 acres in Arkansas, just across the Mississippi River from Greenville, Mississippi. Ruspoli visited the plantation in 1894 and he and Austin Corbin agreed that Ruspoli would have recruited and sent 100 families a year for 5 years to work in the Sunnyside Plantation.

The first group came in 1895, the second in 1896, and immigration to the Delta continued until 1921. The Italians discovered that life on the Sunnyside Plantation was extremely difficult because there were mosquitoes transmitting the malaria, and because of floods: the plantation was on the crescent of Lake Chicot, where the river Mississippi joins the lake, and there were floods every year. In some cases entire families died of malaria.

In addition to the problems caused by malaria and floods was the fact that planters (padroni) treated the Italian immigrants the way they had been accustomed to treating their Black slaves.

We don't know the exact connection between Ruspoli and Austin Corbin: some people think that one of Ruspoli's wives was a sister of Corbin, but we are not sure about that.

The Delta Italians Vol. II is a supplement to the first book but also contains the Sicilian story…

I began collecting material for my book The Delta Italians after my first trip to Italy in 1972. About 1990, although I did not have the complete story, I realized I should put what I had collected into print or all would be lost. My first book consisted of a history and family stories of those Italians recruited for cotton plantations of the Arkansas and Mississippi Delta. Volume II supplements the first book but also contains the immigration stories of other Italians who settled in the Delta, those not recruited for cotton plantations.

I have received more compliments for having written these two books than anything else I've done in my life, because descendants of Italian immigrants appreciate the preservation of their history, although only bits and pieces remain. Most of our people had no formal education, consequently they could not read or write. Most of what I was able to obtain is oral history. However, we do have a little written history.

For example Giuseppe "Peppe" Rocconi wrote about his family: he went to school, at least elementary school. His hope was to get an education. He had even considered becoming a priest so he could further his education.

The Sicilians and Southern Italians had a totally different history than our people, both in Italy and in the South of the United States. In Italy they were under foreign rule for centuries. Sicilian men generally emigrated alone and got settled before sending for their wives and children.

Most of those who eventually settled in the Delta came by way of New Orleans. Some worked around the Port of New Orleans and learned the fruit and vegetable business. Others worked in the sugar cane fields of Louisiana. Eventually some made their way up the Mississippi River to cities like Natchez and Greenville and then moved inland to smaller Delta towns. At first they peddled household goods on foot around the countryside. When they could afford a horse or mule and a wagon they peddled their goods from “rolling stores”. They later set up fruit stands and small grocery stores. When they were settled they sent for their wives and children. Discovering that locals liked their Italian cooking, the Sicilians began selling cooked food in their grocery stores. That was the birth of cafes that Sicilians set up in most Delta towns. The little town of Shaw where I grew up had three Sicilian cafes.

Italians recruited for cotton plantations came as families: they were farmers, consequently they needed their wives and children to work in the cotton fields.

I did not have to miss school but most farm children of my generation and older had to miss several weeks of school in the fall and springtime to work in the cotton fields. Since Sicilians lived in towns their children had greater educational opportunities and entered the professions earlier than children of Italians who settled on farms.

You are a first-generation son of a Delta Italian, right? Yours is a pretty interesting story …

I was born from elderly parents and I'm one of the few of my generation who actually speaks and understands Italian...if I speak Italian you would detect a lot of Marchigiano's dialect! My first visit to Italy in 1972 opened a new world for me. Both of my parents were deceased. There were so many questions I wanted to ask them. I was able to meet my Uncle Antonio, my father’s brother, the only uncle I ever met. My Uncle Pacifico had died just a few months earlier. I also met many first cousins.

My mother was from the area of Ostra, not far from Senigallia. She was married to a man named Cesare Mancini and they lived in an extended family: the mother and the father and married children, all lived in one house. Cesare Mancini was looking for a better life and was anxious to come to the USA, but there was also another reason why they moved to the USA: my oldest half-brother, Marino or Mike, as we called him, was getting into his teenage years and people at that time were looking to avoid their children going to the first world war. Cesare and one of their 5 children died shortly after their arrival in Mississippi.

Marino was my mother’s only support after her husband’s death because she was left with 4 children in a remote area of northwest Mississippi where there was only one person who spoke Italian, the Sicilian manager of the plantation.

My father also lived in an extended family. In the home there were my grandfather Serafino and his family and also my grandfather’s brother Francesco and his family. At one time there were 35 living in one house. They lived and worked on the farm of a lady (la marchesa) who lived in a villa in Montemarciano. I think my father came to the United States because he wanted to get married. At that time the “padrone” could determine whether a man could marry. My father left for the United States immediately after his marriage, within a week.

My mother remained on the plantation near Marks, Mississippi, for three years. Having lost her husband Cesare Mancini and a child, she and her remaining four children found life extremely difficult. Angelo Fioranelli, a relative of her deceased husband, brought her and her children to the Heathmann Plantation located near Greenville, Mississippi, where a large number of Italian immigrants had already settled. That is where she met my father whose wife had died leaving him with two children, both born in the United States. My parents married after a very brief romance. In fact, my eldest half-sister said they were married before she even knew my father was in the picture. She had never met my father.

Which are the most fascinating stories you discovered?

In a way every Marchigiano’s story is the same story as mine, because we lived similar lives on farms, ate the same kinds of food, worshiped at the same Catholic Church and experienced the same problems as we struggled to become Americanized. When you said "interesting story" I thought of Gigia Sampaolesi Pierini: she is now deceased, but I interviewed her in 1994 when she was in her 90s.

Gigia was born at Sunnyside but she was taken to Italy to live with her grandparents in Montignano when she was about three years old. Then she was sent back to her parents in the United States with a lady named Sabatini and her son, also from the Marche. When they got to New York the Sabatini lady's son was ill and had to be detained in at Ellis Island, and so she was left alone. She was only thirteen years old!

Gigia’s father went from Lake Village, Arkansas, to get her at Ellis Island. A social worker at Ellis Island brought three girls out, sat them on a bench and asked Gigia’s father to pick his daughter. Gigia’s father looked at the girls seated side by side on the bench and decided "well, maybe this one looks like she might be the mine" and it happened that he chose the right one: but Gigia didn't recognize her father.

Another interesting person I already mentioned is Giuseppe "Peppe" Ruconi, who was a friend of my parents. His was one of the few stories that was written: he wrote in Italian, of course. It was interesting because he traced his childhood, his trip to the United States and his life in America.

Italian immigrants recruited for cotton plantations lived very simply but they made it through the Great Depression of the late 1920s and early 1930 better than most other farmers because they were accustomed to making the best of hard times. They had large gardens. They raised chickens, cows and hogs. They made prosciutto, lonza, and salsicce. The Italians preserved every part of the hog without refrigeration. Every home had a “forno” an outdoor oven where bread was baked a week supply at a time. Our houses were very simple structures that barely kept out rain and snow. The early Italian settlers in the Delta moved often, sometimes looking for a better place to live and sometimes sneaking away by night from an owed debt caused by a poor harvest. Every Italian home was identified by a large garden, a large haystack, a “forno” (oven), and a “grotta”, a large hole dug under the house, where meats and canned fruits and vegetables were stored.

Some say that these Delta Italians had a big influence on the Blues… is that true?

On Tribett Road, east of Leland, Mississippi, there was a large house, made up of three small farmhouses attached together, where Black people lived. And there was also a small store that sold a few household supplies. It was called a barrel house because Black people gathered there on Saturday nights to drink, play their Blues music and dance.

As you know, the Blues often has sorrowful sad: what I said in my book was that as the Italians heard the Blues from across the fields they felt the pain that black people felt. Italians shared the sentiments with the black people, but that does not mean that they had any influence on the Blues: so the answer is no, I don't think there was any connection with the Blues.

The Delta Italians’ music was the music they brought from the Marche, music played on the accordion and mandolin. In fact, I believe that the accordion is native to the Marche! We had especially one family, Domenico Biagioli with his children, his nieces and his nephews, who played accordion: we have two accordions, one that belonged to Domenico and one that belonged to his daughter Florinda, that will be given to the Historical Cultural Museum that is going to open here in Jackson, Mississippi, in December 2017!

Are there places that have had or still have a particular importance in describing Italy in Mississippi?

Farming in the Delta has changed drastically since mechanization. When Italians first settled in the Delta there were mostly family farms consisting of 40, 60 or 80 acres. Now there are mostly mega farms consisting of thousands of acres. Cotton was the principal crop. In fact, the first Italian settlers at Sunnyside were required to plant only cotton, whereas in Italy they had been accustomed rotating crops. Cotton is still one still one main Delta crops but most of the fertile Delta land is planted in soybeans, corn and rice.

Today there are few Italian farmers and they usually have large farms. They own some but lease a large portion of the land they farm. Some Delta Italians who have remained in farming are the Reginelli, Muzzi, Santucci, Rizzo, Aguzzi, Agostinelli, Baioni, Borgognoni and Noe. Blacks still make up a majority of the Delta population but few work on farms.

One might find a café or restaurant here and there that was founded by a Sicilian family. In Greenville there is the widely known Doe’s Eat Place still owned and operated by the Signa family. There are Giardina’s and Lusco’s in Greenwood and Vince’s in Leland.

Although many of us have attempted to hold on to our Italian heritage, after a century or longer there is little left that is purely Italian. We have not retained purely Italian communities like San Francisco, Chicago, St. Louis and larger cities on the East Coast. Most of our surnames have remained unchanged, there are a few Bocce teams and most of us have remained faithful to the Catholic faith. The only thing that remains purely Italian in the Delta is the enormous pride we have for our Italian heritage!

You may be interested

-

“The Hill” St. Louis’ Little Italy

When the fire hydrants begin to look like Italian flags with green, red and white stripes,...

-

A Week in Emilia Romagna: An Italian Atmosp...

The Wine Consortium of Romagna, together with Consulate General of Italy in Boston, the Ho...

-

An Unlikely Union: The love-hate story of Ne...

Award-winning author and Brooklynite Paul Moses is back with a historic yet dazzling sto...

-

Davide Gambino è il miglior "Young Italian F...

Si intitola Pietra Pesante, ed è il miglior giovane documentario italiano, a detta della N...

-

Emanuele: cervello d'Italia al Mit di Boston

Si chiama Emanuele Ceccarelli lo studente del liceo Galvani di Bologna unico italiano amme...

-

Italian American Culture Night

Tuesday, April 14 - 6.30 pm EDTSt. James Church Rocky Hill - 767 Elm St, Rocky Hill,...

-

Polisena delivers address as state lawmakers...

"Italian-Americans came to our country, and state, poor and proud," Johnston Mayor Joseph...

-

The “Little Italies” of Michigan

In doing reseach for this post, I was sure that Italian immigrants found their way to Detr...